Learn Simple And Compound Interest

Interest is defined as the cost of borrowing money, and depending on how it is calculated, can be classified as simple interest or compound interest

Simple interest is calculated only on the principal amount of a loan. Compound interest is calculated on the principal amount and also on the accumulated interest of previous periods, and can thus be regarded as “interest on interest.” This compounding effect can make a big difference in the amount of interest payable on a loan if interest is calculated on a compound rather than simple basis. On the positive side, the magic of compounding can work to your advantage when it comes to your investments, and can be a potent factor in wealth creation. While simple and compound interest are basic financial concepts, becoming thoroughly familiar with them will help you make better decisions when taking out a loan or making investments, which may save you thousands of dollars over the long term.

Simple Interest

The formula for calculating simple interest is:

Simple Interest = Principal x Interest Rate x Term of the loan

= P x i x n

Thus, if simple interest is charged at 5% on a $10,000 loan that is taken out for a three-year period, the total amount of interest payable by the borrower is calculated as: $10,000 x 0.05 x 3 = $1,500.

Interest on this loan is payable at $500 annually, or $1,500 over the three-year loan term.

Compound Interest

The formula for calculating compound interest is:

Compound Interest = Total amount of Principal and Interest in future (or Future Value) less Principal amount at present (or Present Value)

= [P (1 + i)n] – P

= P [(1 + i)n – 1]

where P = Principal, i = annual interest rate in percentage terms, and n = number of compounding periods.

Continuing with the above example, what would be the amount of interest if it is charged on a compound basis? In this case, it would be: $10,000 [(1 + 0.05)3] – 1 = $10,000 [1.157625 – 1] = $1,576.25.

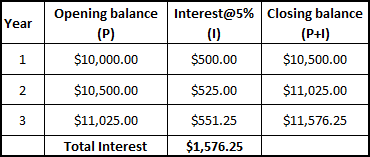

While the total interest payable over the three-year period of this loan is $1,576.25, unlike simple interest, the interest amount is not the same for all three years, because compound interest also takes into consideration accumulated interest of previous periods. Interest payable at the end of each year is shown in the table below.

Compounding Periods

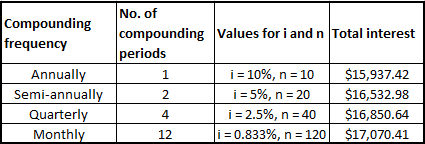

When calculating compound interest, the number of compounding periods makes a significant difference. The basic rule is that the higher the number of compounding periods, the greater the amount of compound interest. So for every $100 of a loan over a certain period of time, the amount of interest accrued at 10% annually will be lower than interest accrued at 5% semi-annually, which will in turn be lower than interest accrued at 2.5% quarterly.

In the formula for calculating compound interest, the variables “i” and “n” have to be adjusted if the number of compounding periods is more than once a year. That is, “i” has to be divided by the number of compounding periods per year, and “n” has to be multiplied by the number of compounding periods. Therefore, for a 10-year loan at 10%, where interest is compounded semi-annually (number of compounding periods = 2), i = 5% (i.e. 10% / 2) and n = 20 (i.e.10 x 2).

The following table demonstrates the difference that the number of compounding periods can make over time for a $10,000 loan taken for a 10-year period.

Associated Concepts

In this section, we introduce some basic concepts associated with compounding.

Time Value of Money

Since money is not “free” but has a cost in terms of interest payable, it follows that a dollar today is worth more than a dollar in future. This concept is known as the time value of money, and forms the basis for relatively advanced techniques like the discounted cash flow (DCF) analysis. The opposite of compounding is known as discounting; the discount factor can be thought of as the reciprocal of the interest rate, and is the factor by which a future value must be multiplied to get the present value.

The formulae for obtaining the future value (FV) and present value (PV) are as follows:

FV = PV (1 +i) n and PV = FV / (1 + i) n

For example, the future value of $10,000 compounded at 5% annually for three years:

= $10,000 (1 + 0.05)3

= $10,000 (1.157625)

= $11,576.25.

The present value of $11,576.25 discounted at 5% for three years:

= $11,576.25 / (1 + 0.05)3

= $11,576.25 / 1.157625

= $10,000

The reciprocal of 1.157625, which equals 0.8638376, is the discount factor in this instance.

Rule of 72

The Rule of 72 calculates the approximate time over which an investment will double at a given rate of return or interest “i”, and is given by (72 / i). It can only be used for annual compounding.

For example, an investment that has a 6% annual rate of return will double in 12 years.

An investment with an 8% rate of return will double in 9 years.

Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR)

The compound annual growth rate (CAGR) is used for most financial applications that require the calculation of a single growth rate over a period of time.

For example, if your investment portfolio has grown from $10,000 to $16,000 over five years, what is the CAGR? Essentially, this means that PV = -$10,000, FV = $16,000, n = 5, so the variable “i” has to be calculated. Using a financial calculator or Excel spreadsheet, it can be shown that i = 9.86%.

(Note that according to cash flow convention, your initial investment (PV) of $10,000 is shown with a negative sign since it represents an outflow of funds. PV and FV must necessarily have opposite signs to solve for “i” in the above equation).

Real-life Applications

The compound annual growth rate (CAGR) is extensively used to calculate returns over periods of time for stock, mutual funds and investment portfolios. The CAGR is also used to ascertain whether a mutual fund manager or portfolio manager has exceeded the market’s rate of return over a period of time. For example, if a market index has provided total returns of 10% over a five-year period, but a fund manager has only generated annual returns of 9% over the same period, the manager has underperformed the market.

The CAGR can also be used to calculate the expected growth rate of investment portfolios over long periods of time, which is useful for such purposes as saving for retirement. Consider the following examples:

1. A risk-averse investor is happy with a modest 3% annual rate of return on her portfolio. Her present $100,000 portfolio would therefore grow to $180,611 after 20 years. In contrast, a risk-tolerant investor who expects an annual return of 6% on his portfolio would see $100,000 grow to $320,714 after 20 years.

2. The CAGR can be used to estimate how much needs to be socked away to save for a specific objective. A couple who would like to save $50,000 over 10 years towards a down payment on a condo would need to save $4,165 per year if they assume an annual return (CAGR) of 4% on their savings. If they are prepared to take a little extra risk and expect a CAGR of 5%, they would need to save $3,975 annually.

3. The CAGR can also be used to demonstrate the virtues of investing earlier rather than later in life. If the objective is to save $1 million by retirement at age 65, based on a CAGR of 6%, a 25-year old would need to save $6,462 per year to attain this goal. A 40-year old, on the other hand, would need to save $18,227, or almost three times that amount, to attain the same goal.

CAGRs also crop up frequently in economic data. For example, China’s per-capita GDP increased from $193 in 1980 to $6,091 in 2012. What is the annual growth in per-capita GDP over this 32-year period? The growth rate “i” in this case works out to an impressive 11.4%.

Points to consider

Make sure you know the exact annual payment rate (APR) on your loan, since the method of calculation and number of compounding periods can have an impact on your monthly payments. While banks and financial institutions have standardized methods to calculate interest payable on mortgages and other loans, the calculations may differ slightly from one country to the next.

Compounding can work in your favor when it comes to your investments, but it can also work for you when making loan repayments. For example, making half your mortgage payment twice a month, rather than making the full payment once a month, will end up cutting down your amortization period and saving you a substantial amount in interest.

Compounding can work against you if you carry loans with very high rates of interest, like credit-card or department store debt. For example, a credit-card balance of $25,000 carried at an interest rate of 20% - compounded monthly - would result in a total interest charge of $5,485 over one year or $457 per month.

The Bottom Line

Get the magic of compounding working for you by investing regularly and increasing the frequency of your loan repayments. Familiarizing yourself with the basic concepts of simple and compound interest will help you make better financial decisions, saving you thousands of dollars and boosting your net worth over time.